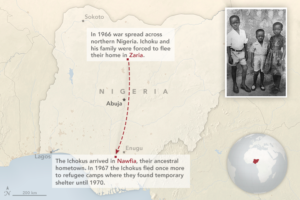

In 1968, Charles Ichoku was a skinny nine-year-old scouring the jungle in southern Nigeria—a refugee looking for his next meal. A bloody civil war had forced Ichoku’s family to flee their home in Zaria, a city in northern Nigeria, for Nawfia, a village in the south where his parents were born and raised.

For three years, Ichoku, his parents, and five brothers and sisters holed up in remote schools that had been converted into refugee camps. The forest cover around the camps and villages was dense enough to ward off advancing ground troops; it did not necessarily deter aircraft or missiles. Life was strange. Schools were closed; food was almost always scarce.

In the midst of war, Ichoku took solace in the natural world. “I was attracted to the order I found in nature,” he said. “Things fit together in a way that made sense.”

Nearly 50 years later, Ichoku still finds himself looking for order and sense in nature, though for very different reasons and from a very different perspective. As a senior scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Ichoku uses satellites to study fires. His latest project has brought him back to the region where he grew up, a place where more fires burn per square kilometer than virtually anywhere on Earth.

Read the full story at

NASA Earth Observatory, August 2016